The Rock Climbers Training Manual describes four types of forearm training that serious climbers will want to have easy access to in their regular training facility, whether it be home wall or local bouldering gym. RCTM training refers to climbers who follow the general recommendations of the Anderson brothers, as outlined in their RCTM book. Strength training is performed on a hangboard so it is not discussed here, although gyms would be wise to follow the Anderson brothers suggestions on set up of good hangboard areas [corrected link address]. The remaining three types of climbing training are ARC, power, and power endurance. Here are my thoughts on how route setting in both home walls and gyms can best facilitate these activities.

Bouldering for ARC/MSS: ARC training involves staying on the wall for long periods of time and requires alternative hand and foot sequences to allow climbers to manage their pump while climbing at 10% to 40% of their maximum effort. Traverses, with integrated upward problems and restful down climbs should be the staple in better training gyms. This does not mean filling an entire bouldering area with such traverses, but gyms should set aside a section of the facility with problems that are designed to work together as a larger system of movement options appropriate to the grades needed for ARC training. Gyms with auto-belays or treadwalls can apply the same principles behind hold layout to those surfaces.

However, well designed training areas with integrated sets of boulder problems have an advantage of allowing multiple climbers to use the resource at once, assuming they can coordinate on direction and pacing. In our little Dojo (500 square feet of climbing surface) we are able to accommodate four simultaneous climbers without too much trouble.

Ideally, an ARC area should also have sections with extremely dense hold layouts, such that climbers can also create their own memorized problems that allow them to tailor their workouts to make them more specific to their goals. The ARC area also needs challenging footholds and diverse hold types to allow climbers to engage in technical skill exercise and otherwise practice better climbing during their long sessions on the wall. ARC training also requires areas with good rests, so if your ARC area is steep like ours, you need to have some bomber holds scattered throughout, and should take advantage of dihedrals and aretes for rest stances. Beginning and intermediate climbers are the least likely to train ARC in a gym, and this is partly because there are not enough decent rests for climbers in the 5.10 and lower range to recover on vertical and slightly overhanging walls. These are the climbers whose performance would benefit the most from following the RCTM combination of ARC and skill training recommendations.

Our setup: Even with limited space a good set of integrated traverses will allow you to create high quality ARC training resources. Our Dojo is a small bouldering room (26ft long by 20 wide at one end and 10 wide at the other). Our layout allows loops that can include roof traverses as well as restful stances in dihedrals and on a couple of less steep sections. Starting near the clock we have 4 traverses, and all are about 50 to 60 hand moves long.

- Any hold (5.10ab)

- Mercy the Pabst (5.11a)

- Orange mustache (5.12a)

- Blues Clues (~5.12b) technical problem with limited foothold options

I use a combination of all 4 of these options for my ARC training by moving in and out of easier or harder sections of each of the traverses in order to cultivate different intensities and raise different technical challenges. At my current level I primarily use the 11a, and add in splashes of harder and easier sections to keep it interesting.

Bouldering for power: There are four great resources for power training: campus boards, well designed bouldering areas, system walls, and Moonboards. The Anderson brothers have great suggestions on campus board design, including a nice description of a mini campus board setup, suitable for folks with limited home wall space (see How to build a campus board). A good training gym will already have a campus board, but some additional design considerations should go into the setup of the bouldering, system wall and moon wall with a mind for allowing RCTM climbers to create limit problems that meet their training needs.

Power training on campus boards: the Anderson brothers describe this well, and they also make it clear that folks with lingering injuries, especially elbow injuries should NOT power train with campus boards until those injuries are fully cleared up. This means that many active training climbers will need to train power in another way, and that is the limit problem.

A limit problem (see Anderson and Anderson, 132) should be only 1 or 2 or, at most 3 moves long, and the moves should be so hard that the climber has to work across multiple attempts to even complete a single move. These should be "drop the clutch" hard, but set up on holds that are as non-injurious as possible.

Power training limit moves on bouldering walls: The definition of a limit problem implies that given the angle of the wall, and given the training level of the climbers, you will need some futuristic hold options. These should allow training climbers to identify limit problems on relatively comfortable holds that are seriously hard to use on wall angles similar to those where route cruxes appear in their goal routes/problems. Open hand crimps and thin pinches are some of the best candidates because they can be difficult while minimizing injury risk and wall space. Slopers may be central to some climbers goals, but they make less ideal candidates for limit problems because they may depend too much on conditions to be ideal for training. Slopers also take up a lot of wall space, and if you set up limit training zones, you will want to have an array of related holds at slightly different levels of intensity. This is easiest to accomplish with openhand crimps and thin pinches. In summary, for route setting purposes this means that at least for the higher end climbers, there will need to be areas with collections of related holds, at slight gradations of differing difficulty that seem dauntingly hard. Or at least, there are hold concentrations that are hard to use and have sufficiently bad feet nearby to to make the moves fully intense.

Power training limit moves on system walls is primarily an option for climbers who are training at lower levels of difficulty. System walls are typically composed of medium challenge holds, and are not usually extreme enough to make compelling limit moves for the top end climbers. For such climbers, campus boards and Moonboards will make better options.

(photo from three rock blocks)

Our setup: Currently, our Dojo is set up with three limit move areas (30 degree, 50 degree, and 70 degree walls). However, none of these are really suitable for advanced climbers because not enough of the holds are difficult/intense enough. For example, this is the 30 degree wall, and this section would benefit from about 15 more holds that are very difficult to use. Edit: I have since added several holds, but still could stand to have more limit holds on this angle. Here is the updated photo:

I hope to add more challenging holds soon, build a small campus board, and eventually, I hope to build a version of a Moonboard at 25 degrees in the downstairs of our garage where the ceiling is over 9 feet high. The pseudo Moonboard will allow us to create limit moves that involve powerful upward movements at an angle that is simply not possible in our low ceiling attic. This would help simulate many of the crux sections at local crags like the New and the Red.

Bouldering for power endurance: power endurance is the easiest dimension to integrate into the route setting of any gym. Power endurance training involves making repeated attempts at problems with continuous difficulty that demands powerful holds, without rest, for 15 to 30 moves in a row. This problem is then repeated after a brief rest period of only 1 or 2 minutes. Problems of about 20 to 26 hand moves are ideal for most training purposes. Once again, the angle should be as specific to the routes/problems in the climbers goal set. The problems should also have slight options for hands or feet that allow climbers to diverge slightly to raise or lower the difficulty of the moves to maintain exertion right at the limit for the full number of moves.

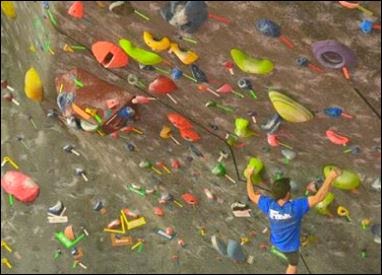

(Jay Bone's photo from Flagstaff comp)

Power endurance training on normal gym bouldering problems. Assuming the problems are of the right length, or that they can be linked to get the right hand move length, then it seems like not much change needs to be made to standard gym set ups. However, it is often the case that climbing gyms set problems primarily for entertainment, and the setting program strives to represent the full range of challenges present in bouldering, including things like commitment, confronting fear etc. These issues, while important in a developmental and entertainment sense, get in the way of the training value of the climbing resource. Boulder problems that are created to facilitate power endurance training need to take fall safety and height into careful consideration and ideally, will be set in a way that minimizes danger and reduce fall distances, or concentrate fall risk over well cushioned landings.

(photo, Rene K-A)

The Shop III is a great example of an ideal power endurance training facility, that has some low and some tall problems, but the landing surface is very well cushioned, minimizing the risk of injury from falls.

Power endurance training on super dense walls. The classic super dense wall is ideal for this type of training. This image from a recent post in the FB route setting group illustrates the type of density that we all would like. However, one shortcoming of this wall, at least for the North American sport climber who trains indoors is the preponderance of large slopers and pinches and the generally large and imprecise footholds these hold types present. If you are training to reach outdoor sport climbing or bouldering goals, this wall would be better composed with a higher concentration of open crimps, thin pinches, technical feet, and occasional pockets

(photo, VOLNY)

Training indoors should be specific to the type of goal routes that the climbers at that facility aspire to. Even for folks who climb primarily at the RRG, this example photo seems to over rely on pinches and slopers in a way that reduces the specificity of the training. A middle ground (like the Shop III) is between the holds on this wall those typical of a moon wall would greatly increase the training value of this facility for sport climbers in most of North America (Maple Canyon an exception).

Our setup: we have several problems and variants that can be integrated with the stand traverses to make ~24 move problems intense for most climbers at the Dojo. There is a direct finish on the 12a traverse which bumps up the route with three boulder problem sections. Also, because the wall is low, it is easy to push limits with little concern for injury. The 50 degree wall with it's system wall sections has plenty of potential for making PE move sections to tack onto and intro traverse.